Hesketh Bell

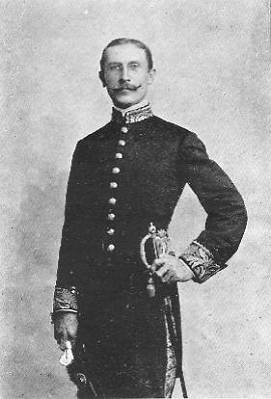

Report on the KalinagoHenry Hesketh Bell was made administrator of Dominica in 1898 at age 34.

During this time he was responsible for a number of changes to the island including, allocating land for the Kalinago People who had long been displaced since the Europeans began to settle.

Photo: Hesketh Bell in 1898. Courtesy www.lennoxhonychurch.com

Related Links

A History of Pirates in Dominica

Dominica’s Heritage A – Z

Government House

Dominica,

29th July, 1902

Sir,

On more than one occasion you have expressed a desire to be informed as to the present condition of the Caribs of Dominica, and I now venture to submit the following report upon the last surviving remnant of these West Indian aborigines.

I trust I may not be considered to be overstepping the bounds of an official despatch if I preface my description of the Caribs, as they are to-day, by short sketch of such meagre items of their history as are still available.

Cuba, San Domingo, Jamaica, and the other larger islands in the West Indies, appear to have been inhabited, at the time of their discovery, by a mild and timid race, generally called Arouagues by Labat, Du Tetre and other French historians of the 17th century. The smaller islands, stretching from St. Thomas to Tobago, seem, on the contrary, to have been peopled, at that period, by a warlike and indomitable race of savages, collectively known as “Charaibes” or “Caribs,” who heroically resisted every attempt at colonization on the part of European intruders, and preferred death to the withering slavery that became the fate of the natives of the larger islands. So stubborn was the resistance offered by these dauntless savages that settlements in the places held by them were not effected until long after the other islands had become flourishing plantation and civilized communities.

The origin of these “Caribs” has been the subject of considerable speculation. Local traditions assert that the primitive inhabitants of the smaller islands, like those of the larger Antilles, were tribes of the great “Arrowak’ or “Arouague” nation and that, at some period which cannot now be ascertained, the Caribs arrived in fleets of canoes from unknown parts, and over-ran the Leeward and Windward groups. They transmitted to their daughters the Arouague language, which thenceforward became a dialect peculiar to the females, while the sons spoke only the language of their Carib fathers. Some writers have inclined to the belief that the invaders came from the north, while others have favoured the theory that they issued from South America. Be that as it may, the Carib type, even in the remnant that survives to-day, shows an unmistakably Mongolian character and it would be hard to distinguish a Carib infant from a Chinese or Tartar child. They have the same straight, coarse, blue-black hair, oblique eyes, prominent cheek bones, and rather flat noses, white the colour of the true Carib is so light a copper as to be almost yellow. It is an interesting fact that some 20 years ago, a Chinaman who, haphazard, found his way to Dominica drifted to the Carib Reserve. He declared that they were his own people and married one of the women of pure-breed. By her, he has had three daughters, and while they are, presumably, half-Chinese, half-Carib, they show no variation whatever from the type of the other pure-bred natives in the Reserve.

The advent of the Caribs in the Lesser Antilles cannot have happened many centuries before the appearance of Europeans on the scene, because even though the original Arouague had completely disappeared from these islands when Columbus discovered them, still the Carib population was very small and much scattered. They do not appear to have had any very large settlements anywhere, and it was rare to find a “Carbet” of more that 20 to 30 huts. Their villages were always on the seashore, and then they seem to have only penetrated into the mountains and valleys of the interior when in search of birds and small game, which they killed with bows and arrows. Fish was their principal food, and the skill displayed by them in the management of their frail canoes especially attracted admiration of European travellers. In these narrow barks, fashioned out a single log of the Gommier tree, the Carib did not fear to race the open Atlantic, and they appear to have thought little of venturing as far south as the Spanish Main, and as far north as San Domingo in quest of victims for their cannibal feasts.

The characteristic which most keenly attracted early travellers among the Caribs was their remarkable passion for human flesh. It appears that they rarely consumed members of their own tribe, and, in order to satisfy their craving, they would put to sea in their frail dug-outs and paddle hundreds of miles in quest of the Arrowak who still survived in the greater islands of the north and south and on the mainland. Peter Martyr learnt from the interpreters that the Caribs ruled over many of the neighbouring islands; that they cruised in large canoes, harassed the peaceable inhabitants, ate the men, carried off the women, “emasculated the boys whom they seized, and those who were born of their captives, fed them fat, and, at their festivals, devoured them. When the men go forth of the land a man-hunting, the women manfully defend their coasts against such as attempt to invade them.” It is believed that De Foe placed the scene of his inimitable tale Tobago, and that the mild “Man Friday” was one of a hapless lot of Arrowaks whom a party of Caribs from Guadeloupe or Dominica had captured on the Spanish Main, and were carrying north for the delectation of the tribe.

The arrival of Europeans upon the scene did not diminish the man-eating propensities of these formidable savages. On the contrary, the Spanish settlements were constantly raided from the moment they were started, and the colonists were kept in continual terror by the attacks of the “Indians”. It is probable that the Caribs of the various islands coalesced on these occasions so as to make their descents in greater force, for, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the cannibals are stated to have “in our time violently taken out of the said island Sancti Johannis (Puerto Rico) more than 5,000 men to be eaten.”

Though Spaniards, Frenchmen, Dutchmen, Negroes, or Arrowaks were all meat to them, yet they seem to have shown an interesting preference to certain nationalities. Davis, for instance, in his “history of the Carribby islands,” tells us that “the Caribbeans have tasted of all the nations that frequented them, and affirm that the French are the most delicate, and the Spaniards ate hardest of digestion.” Laborde, also in one of his jaunts in St. Vincent, appears to have overtaken, on the road a communicative Carib who was beguiling the tedium of his journey by gnawing at the remains of a boiled human foot. This gentleman only ate Arrowaks. “Christians,” he said, “gave him the belly-ache.”

Peter Martyr gives an interesting description of a Carib homestead. “Forasmuch as have made mention of their houses, it shall not be greatly from my purpose to describe in what manner they were builded: they were made round like bells or round pavilions, the frame is raised of exceeding high trees, set close together, a fast rampired in the ground, so standing aslope and bending inward that the tops of the trees join together, and bear one against another, having also within the house certain strong and short props or posts which sustain the trees from falling. They cover them with leaves of date trees (?) and other trees strongly compact an hardened, wherewith they make them close from wind and weather. At the short posts or props within the house, they tie ropes of the cotton of gossampine trees, which grow plentifully in these islands. This cotton the Spaniards call algodon, and the Italians bombazine, and thus they sleep in hanging beds.

“They found also in their kitchens, man’s flesh, duck’s flesh and goose flesh, all in one pot, and others on the spits ready to be laid to the fire. Entering into their inner lodgings, they found faggots of the bones of men’s arms and legs, which they reserve to head arrows, because they lack iron; the other bones they cast away when they have eaten the flesh. They found likewise the head of a young man, fastened to a post, and yet bleeding and drinking vessels made of skulls.”

So frequent and unbearable were the descents of the Caribs on the settlements and plantations in the northern islands that, in 1547, the King of Spain gave special permission to the inhabitants of San Juan to make war upon the Caribs and to enslave them. The natives of Trinidad, Guadeloupe, Martinique (Martinino), Dominica, and Santa Cruz were specially aimed at. These islands appear to have always been the chief strongholds of the Caribs, and their mountains configuration, dense forests, and precipitous defiles doubtless afforded an impenetrable protection against any punitive expeditions that might be despatched against them. Barbados, Antigua, and the other islands or coral formation, were too open and flat to give sufficient shelter, and being untenanted by the redoubtable savages, were chosen for the first footholds of the European settlements.

In spite of the united efforts of the English, Spanish, French and Dutch colonists, the war of extermination declared against the Caribs led only to indefinite conclusions. The savages seemed eager to take up the gauntlet against intruders from any part of the world, and they redoubled their attacks on the growing colonies of their enemies. Without a sign of warning, their crowded canoes would suddenly round a headland and swarm into the harbour of a peaceful settlement. before the white men could fly to their arms or concert the slightest plan for defence, the crimson-painted savages, yelling like friends, would be in their midst. In an instant the town was in a blaze. Overpowered by numbers, the unfortunate traders and artisans would fall like sheep under the stone hatchets and tomahawks of the Caribs, leaving the shrieking women and children at the mercy of the captors, doomed to a horrible fate in a distant island. Maddened by rum and gorged with plunder, the savages would hasten back to their canoes with their prisoners and loot, and long before the settlers in the neighbouring plantations had been able to gather to repel the attack, the swiftly-padded canoes of the ravishers would be more specks on the horizon far beyond the reach of the rescue or revenge.

Gradually, however, the European settlements became strong enough to guard against such frequent recurrences of these outrages, and ruthless reprisals were made upon Caribs wherever found. They were treated like wild beasts and killed on sight. No efforts were made to take them alive, because as slaves they were valueless. The Dominica Caribs especially showed an indomitable spirit. Du Tertre gives an instance of their untamable nature. He says: “What happened to the English Governor of Montserrat shows clearly the prodigious aversion which this nation (the Caribs) have to servitude; for, on having taken some of them from Dominica, he employed all sorts of means to make them work, but it was impossible for him to subdue them, for though he loaded them with heavy chains to prevent their running away, they nevertheless dragged them to the seaside, to seize any canoe or to look out for some pirogue of their nation, to carry them back to their homes; so that seeing their obstinancy, he had their eyes put out; but this rigour availed him nothing, for they preferred being left to die of grief and hunger to living as slaves.”

Year by year the Caribs found their possessions torn from them and their hunting grounds disappearing before the canefields and coffee plantations of the white man. One by one the northern islands were evacuated, and by the beginning of the 17th century, we find them remaining masters only of Guadeloupe, Dominica and Martinique. Even in these islands, small settlements began to be made at the mouths of rivers and in other localities on the seaboard where the configuration of the country admitted of any easy defence. Thus, in 1633, the French had established so firm a foothold in Dominica that Du Tertre, in that year, was able to give a fair estimate of the number of Caribs were on the island. He declared that there were only 938 off them living in 32 carbets or villages. The French, in that year numbered 349, with 23 free mulattoes and 338 negroes slaves. The whole of the interior of this mountainous and forest-clad island, however, remained in the sole possession of the Caribs, and from their hidden strongholds they would constantly descend to pillage and burn the plantations of the outlying settlers.

In 1635, the Dominica Caribs, in concert with bands from St. Vincent, made a descent upon the French settlers who had laid the foundations of a flourishing colony in Guadeloupe. They numbered 1,500 but were driven off with loss and compelled to sue for peace. In the following year, the French organised a “drive” of the Caribs who still remained in Guadeloupe. The unfortunate savages were swept into the sea and the survivors took refuge in Dominica. Similar energetic action was taken by the colonists in Martinique with the result that the Carib population of Dominica received large additions, and the island thenceforth became the principal stronghold of the natives. so frequent were their attacks on the plantations on the coast, that most of the French settlers abandoned their holdings, and, during the next fifty years the French claim to the ownership of the island was of the most shadowy nature.

From their stronghold in Dominica, the Caribs, gathering strength and numbers, resumed their attacks on the northern islands. Over and over agin were the towns and plantations in Antigua, in particular, being constantly the object of their raids. In 1610, the Dominica Caribs pillaged almost every plantation in that island and carried away with them the wife of governor Warner and her two children. During the following twenty-five years, their incursions were almost an annual occurrence, and we find recorded among those who were borne away into a horrible captivity “Mrs. Carden and children, Mrs. Taylor and children, Mrs. Chew and children, Mrs. Lynch and children, Mrs Lee, wife of Captain Lee, and many other females.” In 1666 the French, who had temporarily been in possession of Antigua, evacuated the island, and their departure was almost immediately followed by another descent of the Caribs from Dominica. On this occasion they proceeded to the house of the Ex-Governor, Colonel Carden, who it is stated, “treated them very kindly and administered to their wants. Upon their leaving, they requested their entertainer to accompany them to the beach, who instantly complied; but the Caribs, more treacherous than the wild beasts that haunt the desert, had no sooner reached the place where their canoes were stationed than they fell upon their kind host, cruelly murdered him, and broiled his head, which they afterwards carried with them to Dominica.”

So hopeless appeared the prospect of any friendly arrangement with the Caribs, that by the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, in 1748, which purported to settle the ownership of al the Lesser Antilles, Dominica was apportioned to neither British nor French, but was specially set apart as a neutral island for the sole benefit of the Caribs. it was stipulated that no European nation should make settlements there, and a native chief was to be recognized as master of the islands. For a considerable period subsequent to this arrangement, the Caribs appear to have remained more or less quiescent, and to refrained from attacking the settlements in neighbouring islands. Later on, we find their alliance being sought by both French and English, and the Dominica Caribs were frequently to be seen fighting on the side off one or other of the contending nations.

Dominica, however, was much too fair and desirable a possession to remain efficiently protected by the provisions of the Treaty of 1748, and the French soon unofficially commenced to resume their small trading stations and plantations on the leeward coast. These encroachments were usually made while the French were “allies” of the Caribs. Gradually, the savages awakened to the danger that menaced them from the increase of these small settlements, friction arose, and the colonists were attacked. They defended themselves vigorously, repulsed the Caribs, and thanks to their foothold on the seaboard, drove the aborigines further and further from their settlements.

The progress of the French was, nevertheless, constantly hampered by the attacks of small British parties. Under the pretence of enforcing the provisions off the Treaty and of protecting the rights of the Caribs, the English would land and burn plantations of the French. If fortune favoured the interlopers, the rights of the Caribs were speedily lost sight of, and the British filibusters would retain possession of the French estates. the Caribs would find that the nationality of the trespassers was the only difference in the case, and that the English took up the aggressions where the French had left them off.

By the ninth article of the Peace of Paris, in 1763, the previous arrangement was set aside. Dominica was defiantly assigned to the British, and a Lieutenant Governor was formally appointed. Though no vigorous steps were taken to develop the new possession, yet the plantations and villages of the settlers continued slowly to spread around the coasts of the island and to creep up the valleys towards the interior. The claims of the Caribs to any of the arable land were now systematically ignored. So long as they kept to their forests and roamed about the mountains of the interior, they were tacitly allowed to live, but the white settlers eagerly looked forward to the day when privation, disease, and violence would wipe them out with the same completeness as has been the case in the other West Indian islands.

So thoroughly were the aborigines considered to have lost all claim to their homes that, in 1750, when Commissioners were appointed by the King to survey the whole island, parcel it out into lots, and sell the same by auction, a paltry reservation of 232 acres, in one block, was alone set apart for the behoof of the unfortunate Caribs. They were probably looked upon much in the lights of so many head of game roaming over the land, to be dealt with according to the pleasure of the purchaser. Those who acquired the lots, at the sale by auction in….London, had, however, reckoned without their hosts. The Caribs, though much reduced in number, were found to have lost little of the indomitable spirit of their ancestors, and they resisted so strenuously, all attempts at cultivation in any of the blocks that were out of the immediate reach of the seaboard, that the purchasers soon found their speculations anything profitable. Assisted by the run-away slaves, who made common cause with them, the Caribs successfully defended their forests and mountains against all comers, while the constant expeditions despatched by the Government on the coastline, so frequently ended in disaster that all efforts to dislodge the Caribs and to cultivate he interior appear, for many years, to have been abandoned. To the stubborn defence made by the natives should be attributed to the fact that, to-day, Dominica is the only island in he West Indies where almost the whole of the interior still remains in primeval forest and entirely undeveloped.

At the latter end of the 18th century the Caribs, in their efforts to get away from the hated intruders, seem to have gradually found themselves congregated at a point on the northeast coast as far distant as possible from Roseau, the principal white settlement. Here, the land being of very poor description and little likely to tempt a colonist, they hoped they might be safe from further molestation and free to follow their own customs. their numbers seem to have been much reduced by the customs. Their numbers seem to have been much reduced by the constant warfare off the two preceding centuries, and, in 1791, the Caribs were reported to compromise not more than 20 or 30 families. It is probable that by this time, their old passion for human flesh must have died out for lack of opportunity and. judging by the meagre references made in the local records to this unconquered remnant of their race, the Caribs appear, thenceforward, to have settled down peaceably in their villages of Salybia and Bataca, and to have remained in their villages of Salybia and Bataca, and to have refrained from further opposition to the white settlers.

A century of peaceful avocations has completely metamorphosed the Carib. Instead of a bloodthirsty, man-eating savage, he is now as law-abiding and mild a subject as any the King has. He no longer paints crimson circles of noucou round his eyes and stripes of black and white over his body, but–and I state it with sorrow–on high days and holidays, he wears a tall hat and a black coat. His Zemis have been scattered among the collections of curios, and instead of yelling round a sacrificial stone, the Carib of to-day goes to confession to the parish priest, and tells his beads with edifying fervour. The picturesque abode depicted by Peter Martyr, where faggots of human bones represented most of the furniture, and a bleeding head hung on a post like a picture, has been replaced by the less romantic, if more comfortable, shingled cabin. The Carib has even lost the art of making the Algodon hammocks for which the world owes a debt of gratitude to his forebears. He sleeps on a bed, like anyone else, and he must be poor indeed if his little shanty contain not at least a couple of chairs and a table. The stone implements, with which in the old days he used to brain an adversary or hollow out his canoe, have long been replaced by the hoe and the axe from Birmingham, while the beautifully sharpened celts that once caused him so much labour to fashion are now only found hap-hazard under some inches of earth, and are greedily snapped up by the neighbouring Negroes as “thunderstones,” accounted passing good for the concoction of “medicine.”

The hundred years of peace and protection have arrested almost att the last gasp, the extinction of this interesting remnant of one of the world’s races. The 20 or 30 families reported at the beginning of the century are still with us to-day, if we count only the Caribs of pure breed, while att the last census, the returns showed, as the population of the Reserve, nearly 400, who claimed to be Caribs. It is to be regretted, from an ethnological point of view, that the breed is suffering much from the admixture of Negro blood. Out of the 400 who are settled on the reserve, I doubt whether more than 120 are full-blooded Caribs, and these undoubtedly the last survivors of their race in the West Indies. the so-called Caribs of St. Vincent are much more akin to Negroes than to their original types, and so early did the fusion between the St. Vincent natives and the Negroes begin, that, even two centuries ago, they were known as the “Black Caribs” in contradistinction to the “Red” or pure-bred savages of Dominica and Guadeloupe. There were never two separate colours of Caribs in the lesser Antilles, as has been stated, and the Negro admixture of the St. Vincent people is proved in Southey’s History of the West Indies by the fact that when the French emissaries, in 1772, tried to rouse the St. Vincent Caribs to an outbreak against the English, they told them that, “as they were mostly descended from a cargo of slaves bound in an English ship to Barbados, but wrecked at St. Vincent, the heir of the owner had obtained an order to sell them as his property.”

When I visited the Carib settlement a short time ago, I found 78 children in the school that had just been established there. Of these, I was able to pick out 26 who appeared to be of pure blood. These children all had extremely bright and intelligent expressions and many of them, in spite of their oblique eyes, were very pretty. Their hair, though very straight and rather coarse, was of a beautiful blue-black. In complexion they varied from brown to a pinfish yellow, and, judging by these specimens, the original Carib must have been a very handsome race. These little children showed remarkable intelligence. Though the school had only been opened a few weeks, some of the little ones, who could not have been more remarkable, as not one of them could speak a word of English.

The Carib language is practically extinct. Rochefort, in an appendix to a work that is now rare, Histoire Naturelle et Morale des Isles Antilles del’Amerique (Rotterdam, 1665), gives a glossary of Carib words, and judging by them the language must have been a singularly harmonious one. For instance: blood, nitta: hair, mitibouri;mouth, niouma;hand, noukabo;foot, nougouti;husband, niraiti;father, baba; wife, liani; & c. & c. A large proportion of the words are given Rochefort end in open vowels, and are remarkably mellifluous. He omits to state, however, whether the language transcribed by him was the one spoken by the Carib men or the one peculiar to women of the nation. If it be the language of the males, which they brought with them from their unknown place of origin, it would be interesting to compare the words given by Rochefort with the dialects still extant among the so-called Caribs of Guinea and the Orinoco.

Two or three old dames were brought to me, in one of my visits to the Carib Reserve, who were supposed to retain some knowledge of the old language, but my faith in the accuracy of their illustrations was shaken by one of them assuring me in patios that the old Carib form of salutation was ” Goomorring.” Generally speaking, “creole patois” is he only dialect used by the Caribs, and I found it to be French of a rather less debased character than that spoken by the Negroe inhabitants of Dominica.

I judged, according to the pronunciation of their name by the aborigines themselves, that the accepted spelling is phonetically faulty. The early writers seem to have been much in doubt on the point, and we find, the French authors calling the “Indians” Charaibes, Caraib, or Carribe, Carribbee, or even crab. In fact, we find even to-day among the Barbadian Negroes, who have a high opinion of themselves, a jingle to the effect that they are “neither Crab nor Creole, but true badian born.” All the Caribs I have met have always pronounced the name as if it were spelt “Cribs,” rhyming with scribe.

The Dominica Caribs are still famous for their canoes and their water-proof baskets, and the manufacture of these comprise their only industries. The long dug-out which, in the old turbulent times, brought terror to the hearts of the first settlers, remains, to-day, exactly the same in shape and character as it appeared to Columbus when he described It in his diary. The straight thick stem of the great gommier tree is always the one selected for the construction of a canoe. The bark is hacked off and the heart burnt into charcoal. heavy stones are piled into the hollow, so as to widen the sides, the ends are both sharpened, and the craft is then ready for the water. In these cranky dugouts, the Caribs venture far into the ocean on fishing expeditions, and though a turn-over may be a common occurrence, the crew, who swim like fish, speedily right their craft and take incident as a matter of course.

Fish is the staple food of the Caribs. They catch enormous quantities, but make no attempt to cure or smoke the surplus. A few of them possess a head or two of the cattle or sheep, and the usual skinny West Indian fowl is generally to be found around their cabins. in spite of the poverty of their land, they raise a sufficiencyof plantations, yams, tannias, and other vegetables common to the tropics. They are excellent woodsmen, and earn such money as they require by cutting native timber and splitting shingles.

It is much to be regretted that, generally speaking, any cash received by them invariably finds its way to the rum shop. No licensed dealer in spirits has been allowed to run a business in the Reserve, but, when on liquor bent, a trudge of many miles will not deter the Caribs. Drink is his besetting sin, and unlike the Negro inhabitants of Dominica, a small quantity of spirits rapidly shows an effect upon him. at Christmas time they especially give way to their love for liquor. For several weeks before the festive season they set to work to manufacture the well-known “Carib baskets” for which a ready sale is always found. A certain number of the tribe are deputed to journey to Roseau with the stock and charged to return with rum and gin. A general jollification follows the receipt of the liquor, and no work is done until the supply has disappeared. I do not, however, wish to give an impression that, like his cousin in the American “Far West,” the Dominican Carib is being wiped out by the curse of drink. On the contrary, circumstances over which he has no control prevent his getting hold of any abundance of intoxicating liquor, and while the inclination to excess is undoubtedly there, the opportunities for gratifying it are few and far between.

Politically, the Caribs are now of no account. With the exception that they are exempted from any direct taxation, they are treated exactly like other natives of the island and have the same privileges. In return for their freedom from taxation, they are required to keep in order the two miles of high road which traverse their Reserve. The Government, however, has always recognized a chief or headman of the Caribs and though he has never received any stipend or other advantage he is supposed to settle petty disputes among his people and to adjust any differences that may arise as to the cultivation of the land held in common.

The present chief of the Caribs is called Auguste Francois, but generally known as “Ogiste.” He claims to be of pure breed, but a marked tendency to a curl in his long black hair has inspired me with suspicions on this score. The Chief’s hut on the Reserve is neither better nor worse than the others. It is a wooden shanty, with a thatched roof and is crowded round by mango trees and coconut palms. When I saw it last, a gorgeous ‘flamboyant” tree, in full bloom, was shedding its scarlet blossoms all over the russet thatch, and many a greater potentate than Auguste might envy him magnificent tints of this surroundings. The Chief’s old wife is blind and their children seem to have all died. A little grand child alone represents the continuance of the dynasty, but unfortunately, she is more Negro than Carib, and moreover, the Salic Law prevails.

In spite of the peaceful air of the settlement, it is not without its “burning questions,” and the Caribs are much exercised respecting the “Bastards.” Under this uncompromising denomination, are comprised all those who not be a single pure-bred specimen left to show the true type of this interesting people. Unfortunately, the younger generation show the true type of this interesting people. Unfortunately, the younger generation show but little pride of race. The men brought Negro women into the Reserve and have married them. Many of the Caribs girls have taken Negro husbands. This process has been going on for many year, and the old Caribs see the race dying out, while the privileges in the Reserve originally accorded to them and to their ancestors are being monopolized by a mixed breed whose numbers yearly increase.

In will now deal with one or two matters and suggestions connected with the Caribs, which I hope may have your favourable consideration.

Although, for over a century, the district now occupied by the Caribs has always been officially recognized as their “Reserve,” no proper grant of the land appears to have been made to either the Chief or to any other proper representatives of the tribe. Though the paltry allotment of 232 acres, in 1750, compromised in lot 60 Byres’ plan, limits of the settlement, I can find no trace of any formal arrangement by which the Caribs were allowed to consider as their own the area now held by them. The very year after Byres had completed the survey of the island, delimiting all the blocks of land that had been sold in London, Dominica was captured by the French, and remained in their possession until 1783, when it was re-taken by the British. It is not impossible that the limits of the Carib Commonage were settled during the French, and remained in their possession until 1783, when it was re-taken by the British. It is not impossible that the limits of the Carib Commonage were settled during the French occupation, but no record of the fact can be granted, and the present boundaries of the Reserve, though generally accepted, are open to considerable doubt. There also reason to believe that neighbouring landowners have, in years past, encroached upon the area which was intended to be reserved for the Caribs, and since I have been in Dominica I have been called upon to settle several disputes as to boundaries.

I have, in preceding pages, reported that most of the land in the Carib reserve is of the poorest description and practically worthless. To the poverty of the soil should, I think, be ascribed to the fact that, generally speaking, these natives grow no produce save the commonest vegetables and foodstuffs, and whenever I have impressed upon them the advisability of planting cocoa, limes and other profitable products, I have always been assured that the land in the Reserve was too arid to grow anything of the kind. some months ago, however, it was brought to my notice that a good many of the Caribs were working plots of land in a valley that appeared to be outside the northern boundary of their reserve, and that they already possessed several flourishing patches of cocoa in the locality. The matter was brought to light through Mr. Wm. Davies the owner of the adjacent plantation “Concord,” who submitted an application for a block of what he described as “Crown lands adjoining his estate.” Mr. “Government Officer” Robinson was sent to inspect the locality and he returned with the report that the land applied for by Mr. Davies was in the actual occupation of the Caribs and was being well cultivated by them. The Caribs, moreover, claimed that the valley does from part of their original Reserve, and they would, I believe, strenuously resist eviction.

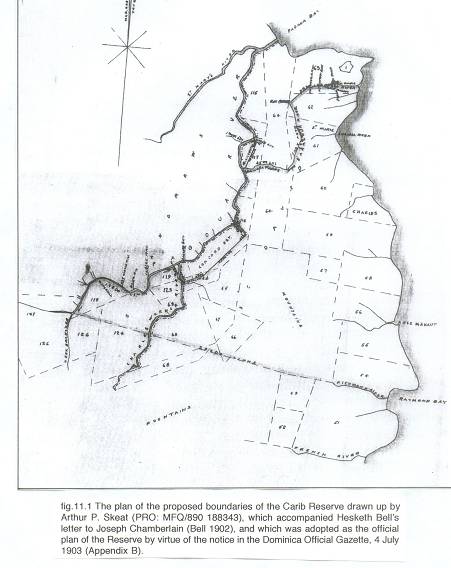

It appeared to me very desirable that the limits of the Reserve should be properly and finally delimited, and I commissioned Mr. A.P. Skeat, a licensed surveyor, to survey the land held by them add to make a plan. He was instructed to follow the recognized boundaries of the Reserve and to adopt, wherever possible, streams, cliffs, and other natural landmarks. He was also authorized to include that part of the Hatton Garden Valley in which their cocoa and other plantations are situated. The land, moreover, was to march with the limits of the neighbouring estates, so as to leave no intervening narrow strips of unoccupied land.

Mr. Robinson, an old Government official, long resident in that district, well acquainted with the Caribs and much respected by them, was associated with Mr. Skeat in making the survey. The Carib Chief and the principal men of the tribe were also consulted, and the proposed boundaries were accepted by them as very satisfactory. They also expressed much gratitude for the proposed liberality of the Government.

I attach hereto the plan of the survey made by Mr. Skeat. It will be seen that the Carib Reserve, within the boundaries now proposed will include 3,700 acres. The inclusion of the valley lands, whose ownership has hitherto been opened to doubt, will probably add three or four hundred acres to the area heretofore held by the Caribs, but I hope this suggested liberality will meet with your sanction. This surviving remnant of the race has been so badly treated in the past that a little kindness to them in the future may not be considered Quixotic. The proposed extension of the Reserve involved only the gift of Crown lands situated in a district which is not likely to attract settlers, and all proper precautions will be taken that the Crown’s disposal of them is open to no counter claim.

I will conclude by recommending to your favourable consideration the advisability of granting to he Carib Chief a small stipend. The present headman, Auguste Francois, is very poor, and has not long to live. I doubt if his subjects contribute much to his support, and I believe that an allowance of £6 a year would be gratefully received. The stipend might be paid out of the Crown Land Funds.

I have, & c.,

H. Hesketh Bell,

Administrator

History, Culture and People